News - There is a long-term risk that Azerbaijan could be fully absorbed by Turkey, which would lead to the imposition of a confederal union.

Business Strategy

There is a long-term risk that Azerbaijan could be fully absorbed by Turkey, which would lead to the imposition of a confederal union.

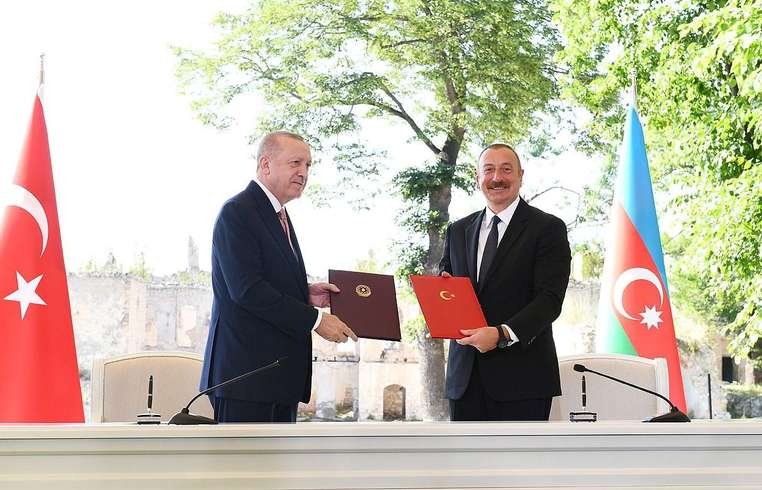

In the previous article we discussed the ongoing and intensifying anti-Armenian policies in Azerbaijan after the 44-day war. The scientific article was prepared by YSU faculty members and researchers at the Institute of Oriental Studies, Levon Hovsepian and Artyom Tonoyan. After that, Hetq spoke about another joint scholarly article by the authors, whose material concerns the Turkish–Azerbaijani relations before and after the 2020 war. The article titled From alliance to ‘soft conquest’: the anatomy of the Turkish-Azerbaijani military alliance before and after the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war was published in the Small Wars and Insurgencies journal. The article is built on information from Azerbaijani open sources. It is behind closed access. The scholarly work presents the development of Turkish–Azerbaijani relations in a comprehensive picture—from the early 1990s to the present. The aim of the article is to reveal the qualitative shifts and changes in the dynamics of military cooperation, assessing their direct and indirect impact on the development of Azerbaijani society’s identity. As early as 1992, Turkey laid the groundwork for its military education in Azerbaijan; eighteen years later, in 2010, an official bilateral cooperation agreement was signed, which, according to the authors, opened a new page in Turkish–Azerbaijani relations. In Azerbaijan the military school had two vectors: Russian and Turkish. After the 2020 war the Turkish vector gained the upper hand. Artyom Tonoyan, in an interview with Hetq, notes that the war demonstrated the logical culmination of a process that had begun earlier. Moreover, this has led to the formulation of a policy heralding the structural, model-like transition of the Azerbaijani army toward the Turkish army. Tonoyan notes that days after the 44-day war the Azerbaijani leader announced that they were steering the army toward the Turkish model: ‘In fact, in several areas Turkey has a very impressive presence. One of them is the army itself. Within the framework of the structural changes in Azerbaijan after the 2020 war, a Turkish general was appointed—if we translate the position literally—the deputy minister of defense of Azerbaijan. In other words, one of his assistants is allocated by quota to Turkey. This is a very interesting, phenomenal phenomenon. It would be hard to say whether there is a second such example in the world. This alone is an indicator of how deep Turkey’s military presence is in the Azerbaijani military system,’ he explains. Before the 2020 war, according to Hetq’s interlocutor, Armenia had Turkologists who spoke about Turkey’s involvement in the war. There were two important factors: first, Turkey’s changed foreign policy. Previously Euro-Atlantic oriented, Turkey shifted its foreign policy course toward the East and the Caucasus. Tonoyan notes that a great deal has been written about this and about neo-Ottomanism in Armenia, including in scholarly literature. Thus, unlike the first Nagorno-Karabakh war, before the 44-day war there was already another Turkey, which had its own ideas and positions regarding the Armenian–Azerbaijani conflict, on the basis of which it was increasing its level of involvement. The second important factor—one that, according to our interlocutor, may be less visible than the first—is Turkey’s economic factor—the changing dynamics of the military-industrial sector within its GDP: ‘When the military industry begins to occupy a noticeable place in your economy, that too is an indicator that affects the country’s foreign policy, pushing it toward aggressive foreign policy to promote conflicts,’ Tonoyan notes. After the 44-day war Azerbaijan’s dependence on Turkey began to grow. Our interlocutor says there are few examples when the stage of victory is shared by the presidents of two countries, whereas Aliyev shared the stage of the military parade with Erdogan. This, Tonoyan says, is an indicator of changing relations and increasing dependence. Furthermore, on 15 June 2021 Turkey and Azerbaijan signed a declaration of allied relations (the ‘Shusha Declaration’), which supplemented the 2010 agreement—lifting Turkish–Azerbaijani relations to a qualitatively new level. ‘There is a real risk of Turkey fully absorbing Azerbaijan in the long run, which would entail the imposition of a confederative union. This discourse is becoming part of the Azerbaijani political agenda, particularly thanks to the support of pro-Turkish figures,’ the article states. Interestingly, after the 2020 war in Azerbaijan a discourse emerged in society about making Turkish the state language; in various places—in state institutions, even in cemeteries—the Turkish flag can also be seen. ‘The second major area, which is a bigger challenge for Aliyev than the military, is public sentiment—the unquestionable dominance of Turkish presence in the ideological orientation of society. According to surveys, 90 percent and more named the Turkish flag as their own flag,’ the oriental studies expert notes. After the war, the slogan ‘One nation, one army’ gained traction in Azerbaijan; analogously, there is a push for ‘One nation, one state language.’ Moreover, in 2022 Azerbaijan opened a Turkish-modeled National Defense University. Artyom Tonoyan says this shows that Turkey’s penetration into Azerbaijan’s ideological field is more tangible than in the military sphere. But in both cases there is a serious stake in Azerbaijan’s sovereignty, as well as in the personal survival and reproduction of its regime. ‘As long as Azerbaijan does not serve Turkey’s interests, it is safe, but if it pursues a more independent policy, it will be endangered. Moreover, this is more dangerous for Azerbaijan because it also borders Russia. The clash of these interests and the competition between them is itself dangerous,’ the Hetq interlocutor notes. Azerbaijan’s state television broadcasts interviews with former and current foreign ministers. The topic is how the 2020 victory was possible. Just before our interview with Tonoyan, an interview with former minister Elmar Mammadyarov had been broadcast. Tonoyan highlights one of Mammadyarov’s statements: when the oil boom began in the late 2000s, the volume of arms acquisitions increased. But, Mammadyarov adds, that alone was not enough to carry out military action. And during that period Azerbaijan intensified sending its servicemen to Turkey for training and military education. Mammadyarov says it took years because the personnel sent were officers. To Hetq’s question whether Azerbaijan will pay a price for Turkey’s involvement in the 2020 victory, given the article’s idea that Turkey will seek to absorb Azerbaijan in the long run, Tonoyan responds: ‘Yes, that is the price. Not only militarily, but more importantly, it makes the society wholly pro-Turkish. If in any country you have a society that shares your ideology, it no longer matters who sits on the throne, because leaving Aliyev on the throne or taking him off again depends on Turkey. Essentially, the ruler becomes a puppet. Aliyev understands this risk very well, but he has used the opportunity of an opened window when Turkish foreign policy shifted. In Azerbaijan there have been two competing ideologies—Azerbaijani-ness and Turkic-ness. When Aliyev used the opened window, he narrowed the Azeri segment. In the end, after the war he achieved a result that is dangerous for him.’ Tonoyan notes that the idea of Azerbaijani-ness is Russian-oriented, while Turkic-ness is Turkish-oriented. Moreover, there is explicit nationalism in Azerbaijan that is Turkic in essence; we can regard pan-Turkism and pan-Turanism as its synonyms. Historically, the idee fixe of Azerbaijani-ness was developed and implanted in the 1930s, during the Soviet era, when it became clear that the Kemal-Lenin alliance had no future. Thus the Turkic orientation of Azerbaijani society was engineered by presenting Azerbaijani-ness as a doctrine. In 1936 a new term appeared—‘Azerbaijan dili,’ meaning ‘Azerbaijani language.’ Tonoyan says there is no such term in pure science or in official discourse; in the 1930s Azerbaijani textbooks all stated ‘Turk dili,’ meaning the mother tongue was Turkic, and in state documents the Azerbaijani state language was also Turkic. Under Stalin, to pull Azerbaijan away from Turkey, Azerbaijani-ness became the dominant political policy; in the minds of locals the idea of being a separate people from Turks began to form. The interlocutor notes that this process ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union, and in 1992 Azerbaijan came to power with a pro-Turkish leadership under Abulfaz Elchibey (his actual surname being Aliyev). Under him the state language again became Turkic, and the Turkic ideological project led to other ethnic groups’ separatist or independence movements. A vivid example was the declaration of the Talish-Mughan Autonomous Republic in the summer of 1993. In the same year, after Elchibey was toppled and Heydar Aliyev came to power, the state language again became Azerbaijani. And after Azerbaijan’s 2023 capture of Artsakh, the Azerbaijani public sphere again discussed making Turkish the state language, but the state has no official involvement in this. ‘In other words, this is not a top-down, but a bottom-up agenda,’ the oriental studies expert emphasizes. He notes that in 1992 Turkism could not take root in Azerbaijan because Turkey’s military factor did not exist in the form it does after 2020. ‘After the 2020 war, Turkic sentiments in society pose a major challenge, which in the short-to-medium term could lead to independence movements or secession,’ the Hetq interlocutor says, adding that for Aliyev to go against the current carries many risks. He therefore has to move very slowly and covertly. Accordingly, it is no accident that he funds local NGOs—granting money to projects that prioritize the spread of Azerbaijani-ness and the promotion of it in schools. ‘Since 2020 they have been repeating the same phrase. You will not find any Azerbaijani official who says that Turkey helped us militarily. They say that Turkey’s support for Azerbaijan has been exclusively political and moral. That is what Aliyev says, and all MPs repeat the same stock line: that in Artsakh only Azerbaijani blood has been shed; we categorically deny that Turkey had any military involvement in Artsakh,’ Tonoyan notes. According to him, this topic fuels major debates in Azerbaijan. Opponents play it well—on camera they pose direct questions to government representatives about whether there was Turkey’s military presence in the 2020 war; effectively, they pressure Aliyev’s subordinates to deny it. Turkey, in turn, emphasizes the fact of its military presence in the 44-day war. In this regard Tonoyan recalls Erdogan’s claim that the Turkish soldier won in Libya and in Karabakh, to which Aliyev’s level responded with a denial that Turkish soldiers shed blood in Azerbaijan. The Orientalist also notes that in February 2024, during his inauguration, Aliyev stressed the importance of having an independent defense industry, aimed at countering Turkey. The Azerbaijani president also stated that they had moved stones such that no one would swallow them, i.e., there would be opponents against them. He says the younger Aliyev remembers the independence movements of the 1990s and is concerned about their repetition. On Azerbaijani public television, interviews with former and current foreign ministers are broadcast. The topic is how the 2020 victory was possible. Just before our interview with Tonoyan, an interview with former minister Elmar Mammadyarov had aired. Tonoyan highlights Mammadyarov’s statement that when the oil boom began in the late 2000s, the volume of arms acquisitions increased. But, Mammadyarov says, that was not enough to undertake a military operation. And during that period Azerbaijan intensified sending its servicemen to Turkey for training and military education. Mammadyarov says it took years because the personnel sent were officers. To Hetq’s question whether Azerbaijan will pay a price for Turkey’s involvement in the 2020 victory, given the article’s idea that Turkey will seek to absorb Azerbaijan in the long run, Tonoyan responds: ‘Yes, that is the price. Not only militarily, but more importantly, the society becoming entirely pro-Turkish. If in any country you have a society that shares your ideology, it no longer matters who sits on the throne, because leaving Aliyev on the throne or taking him off again depends on Turkey. Essentially, the ruler becomes a puppet. Aliyev understands this risk very well, but he has exploited the opportunity created by Turkey’s shifted foreign policy. In Azerbaijan there have been two competing ideologies—Azerbaijani-ness and Turkic-ness. When Aliyev used the opened window, he narrowed the Azerbaijani identity segment. In the end, after the war he obtained a result that is dangerous for him.’ Tonoyan says that the idea of Azerbaijani-ness has a Russian orientation, while Turkicness has a Turkish orientation. Moreover, there is an overt nationalism in Azerbaijan that is Turkic; we can treat pan-Turkism and pan-Turanism as synonyms. Historically, the idea of Azerbaijani-ness was developed and embedded in the 1930s during the Soviet era, when it became clear that the Kemal-Lenin alliance had no future. Thus the engineering of a Turkic-oriented Azerbaijani society was carried out by presenting Azerbaijani-ness as ideology. In 1936 a new term appeared—‘Azerbaijan dili,’ meaning ‘Azerbaijani language.’ Tonoyan says there is no such term in science or official usage; in the 1930s Azerbaijani textbooks all stated ‘Türk dili,’ meaning the mother tongue was Turkish; in state documents the Azerbaijani state language was also Turkish. Under Stalin, to pull Azerbaijan away from Turkey, Azerbaijani-ness became the dominant political policy; in the minds of locals the idea of being a separate people from the Turks began to form. Tonoyan notes that this process ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union, and in 1992 Azerbaijan came to power with a pro-Turkish leadership under Abulfaz Elchibey (his real surname was Aliyev). Under him the state language again became Turkish, and Turkic ideology led to other ethnic groups’ separatist or independence movements. A vivid example was the declaration of the Talish-Mugan Autonomous Republic in the summer of 1993. In the same year, after Elchibey was toppled and Heydar Aliyev came to power, the state language again became Azerbaijani. And after 2023’s capture of Artsakh, the Azerbaijani public debate about making Turkish the state language resurfaced, but the state has not participated. ‘That is, this is not a top-down but a bottom-up agenda,’ the oriental studies expert emphasizes. He notes that in 1992 Turkicness did not take root in Azerbaijan because Turkey’s military factor did not exist in the form it assumes after 2020. ‘After the 2020 war, Turkic sentiments in society pose a major challenge, which in the short- to medium-term could lead to independence movements or secession,’ the Hetq interlocutor says, adding that for Aliyev to go against the current carries many risks. He therefore must act very slowly and covertly. Accordingly, it is no accident that he funds local NGOs—financing programs that place emphasis on spreading Azerbaijani-ness and promoting it in schools. ‘Since 2020 they have been repeating one phrase. You will not find any Azerbaijani official who says that Turkey helped us militarily. They say that Turkey’s support for Azerbaijan has been exclusively political and moral. That is what Aliyev says, and all MPs repeat the same stock sentence: that in Artsakh only Azerbaijani blood has been shed; we categorically deny that Turkey had any military involvement in Artsakh,’ Tonoyan notes. According to him, this topic triggers major debates in Azerbaijan. Opponents play it well, putting direct questions to government representatives on camera about whether there was Turkey’s military involvement in the 2020 war; effectively, forcing Aliyev’s subordinates to deny it. Turkey, for its part, emphasizes the fact of its military presence in the 44-day war. In this regard Tonoyan recalls Erdogan’s statement that the Turkish soldier won in Libya and in Nagorno-Karabakh, to which Aliyev’s level responded with denial that Turkish soldiers shed blood in Azerbaijan. The Orientalist also notes that in February 2024, during his inauguration, Aliyev stressed the importance of having an independent defense industry, aimed at countering Turkey. The president also stated that they have moved stones that no one will swallow—i.e., that there will be adversaries against them. He says the younger Aliyev remembers the independence movements of the 1990s and is concerned about their repetition. On Azerbaijan’s public television, interviews with former and current foreign ministers are broadcast. The topic is how the 2020 victory was possible. Just before our interview with Tonoyan, an interview with former minister Elmar Mammadyarov had aired. Tonoyan highlights Mammadyarov’s statement that when the oil boom began in the late 2000s, the volume of arms acquisitions increased. But, Mammadyarov says, that was not enough to undertake a military operation. During that period Azerbaijan intensified sending its servicemen to Turkey for training and military education. Mammadyarov says it took years because the personnel were officers. To Hetq’s question whether Azerbaijan will pay a price for Turkey’s involvement in the 2020 victory, given the article’s idea that Turkey will seek to absorb Azerbaijan in the long run, Tonoyan responds: ‘Yes, that is the price. Not only militarily, but more importantly, the society becoming wholly pro-Turkish. If in any country you have a society that shares your ideology, it no longer matters who sits on the throne, because removing Aliyev from the seat or keeping him there again depends on Turkey. Essentially, the ruler becomes a puppet. Aliyev understands this risk very well, but he has used the window of opportunity opened when Turkey’s foreign policy shifted. In Azerbaijan there have been two competing ideologies—Azerbaijani-ness and Turkic-ness. When Aliyev used the opened window, he narrowed the Azerbaijani identity segment. In the end, after the war he achieved a result that is dangerous for him.’ Tonoyan says that the idea of Azerbaijani-ness has a Russian orientation, while Turkic-ness has a Turkish orientation. Moreover, there is an openly nationalist current in Azerbaijan that is Turkic in essence; we can regard pan-Turkism and pan-Turanism as its synonyms. Tracing back historically, the interviewee notes that the idea of Azerbaijani-ness was cultivated and embedded in the 1930s during the Soviet era, when it became clear that the Kemal-Lenin alliance had no future. Thus the engineering of a Turkic-oriented Azerbaijani society was carried out by presenting Azerbaijani-ness as a doctrine. In 1936 a new term appeared—‘Azerbaijan dili,’ meaning ‘Azerbaijani language.’ There is no such term in science or official usage; in the 1930s Azerbaijani textbooks all stated ‘Turk dili,’ meaning the mother tongue was Turkic, and in state documents the state language of Azerbaijan was also Turkic. During Stalin’s era, to pull Azerbaijan away from Turkey, Azerbaijani-ness became the dominant political policy; in the minds of locals the idea of being a separate people from Turks began to form. The interlocutor notes that this process ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union; in 1992 Azerbaijan came under the rule of the pro-Turkish Elchibey (real surname Aliyev). Under him the state language again became Turkic, and Turkic ideology gave rise to other ethnic movements for separation or independence. A vivid example was the declaration of the Talish-Mugan Autonomous Republic in the summer of 1993. In the same year, after Elchibey’s overthrow, when Heydar Aliyev came to power, the state language again became Azerbaijani. And after 2023’s capture of Artsakh, the Azerbaijani public discussion about making Turkish the state language resurfaced, but the state has no active involvement in this. ‘This is not a top-down but a bottom-up agenda,’ the oriental studies expert emphasizes. He notes that in 1992 Turkism could not take root in Azerbaijan because there was no Turkey’s military factor in the form it took after 2020. ‘After the 2020 war, Turkic sentiments in society pose a major challenge, which in the short- to medium-term could lead to independence movements or secession,’ the Hetq interlocutor concludes, adding that for Aliyev resisting the flow entails many risks. Therefore he must proceed very slowly and covertly. Accordingly it is no accident that he funds local NGOs—supporting projects that foreground the spread of Azerbaijani-ness and its promotion in schools. ‘Since 2020 they have been repeating one phrase. You will not find any Azerbaijani official who says that Turkey helped us militarily. They say that Turkey’s support for Azerbaijan has been exclusively political and moral. That is what Aliyev says, and all MPs repeat the same stock line: that in Artsakh only Azerbaijani blood has been shed; we categorically deny that Turkey had any military involvement in Artsakh,’ Tonoyan notes. According to him, this topic generates major debates in Azerbaijan. Opponents skillfully push politicians to answer on camera whether there was Turkey’s military presence in the 2020 war; effectively, they compel Aliyev’s subordinates to deny it. Turkey, in turn, stresses the fact of its military presence in the 44-day war. In this regard Tonoyan recalls Erdogan’s remark that the Turkish soldier won in Libya and in Nagorno-Karabakh, to which Aliyev’s level responded with denial that Turkish soldiers shed blood in Azerbaijan. The Orientalist also notes that in February 2024, at his inauguration, Aliyev stressed the importance of having an independent defense industry, aimed at countering Turkey. The president also stated that they had moved such stones that no one would swallow them, i.e., that they expected ongoing antagonism. He says the younger Aliyev remembers the 1990s independence movements and is wary of their repetition. In first captioned photograph: Erdogan and Aliyev after signing the Shusha Declaration, 15 June 2021 (from the Azerbaijani president’s website).